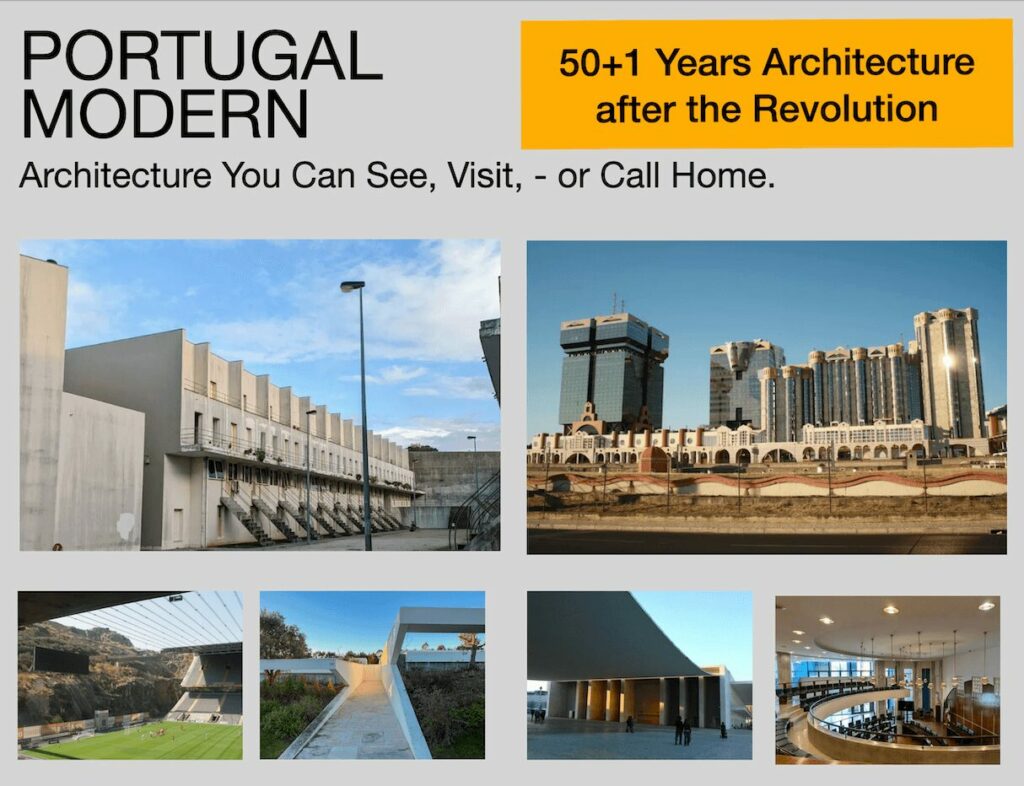

Last Friday, April 25th, Portugal celebrated 51 years since the Carnation Revolution – a turning point that not only changed its political system, but also transformed the way the country builds, imagines, and lives in its spaces.

Over the last five decades, Portuguese architecture has become a global reference, blending social responsibility, design innovation, and artistic excellence.

At the moment, Casa da Arquitectura in Matosinhos (Porto) is presenting a fantastic exhibition called “O que faz falta – 50 anos de arquitetura portuguesa em democracia”.

It’s structured as a journey through five major periods of modern architecture — and I’d like to share it with you.

The timeline of 50 Years of Modern Architecture in Portugal:

• REVOLUTION (1974–1983)

• EUROPA (1984–1993)

•END OF THE CENTURY (1994–2003)

• TROIKA (2004–2013)

• WI-FI (2014–2023)

This was one of the best architecture exhibitions I have seen in Portugal, showing over 50 buildings, most represented with original 3D models.

1. REVOLUTION (1974–1983): Building a New Society – Social Housing

On April 25, 1974, Portugal woke up to a new world.

While the rest of Europe spent the ’50s and ’60s exploring democracy, Portugal stayed frozen in dictatorship — until, finally, what the poet Sophia de Mello Breyner Andresen called “the first full day with a clean slate” arrived.

Architecture didn’t completely start from zero, but it gained a new purpose: create democratic spaces for everyone.

One huge step was the creation of SAAL (Serviço Ambulatório de Apoio Local), launched just a few months after the Revolution.

Now world-famous architects like Álvaro Siza Vieira and Gonçalo Byrne worked directly with local communities to replace slums with real, dignified homes.

Architecture became political — an act of solidarity and a tool for building a better society.

(Bairro da Bouça Porto, Álvaro Siza Photo by Ben)

2. EUROPA (1984–1993): Embracing European Integration – Infrastruct

By the mid-80s, Portugal had secured its democracy — and joining the European Economic Community in 1986 sent a clear message: Portugal was ready to reinvent itself.

Architecture led the way. Across the country, fresh ideas mixed regional traditions with artistic experimentation.

Thanks to European funds, there was massive investment in infrastructure: new universities, schools, cultural centers, and city halls.

At the same time, Portugal’s economy shifted from mainly agriculture to manufacturing and tourism.

One highlight is City Hall of Matosinhos, by Alcino Soutinho, started in 1976 — the first big public building after the Revolution, full of optimism and civic pride.

(City Hall of Matosinhos, Alcino Soutinho, Images by Ben)

Architecture also entered the media spotlight with Tomás Taveira’s Amoreiras Complex in Lisbon — colorful, controversial, and impossible to ignore.

(Amoreiras Complex, Image by Triplecaña Wikipedia)

Meanwhile, universities expanded rapidly: new campuses opened in Lisbon, Aveiro, and Porto.

(Alcino Soutinho, Department of Ceramics and Glass Engineering, University of Aveiro 1988 – 1991, Image by Ben)

Public education, almost non-existent before the Revolution, became a national priority.

A proud moment came when Álvaro Siza Vieira received the Pritzker Architecture Prize in 1992 — the first Portuguese architect ever honored with the “Nobel Prize of Architecture.”

3. END OF THE CENTURY (1994–2003): Optimism and Reflection – Expo, Sport and Villas

The end of the 20th century was a time of excitement and ambition.

The euphoria of big events like Expo ’98 set the mood, and architecture became a key part of Portugal’s new global image.

At Expo ’98, Álvaro Siza’s stunning Pavilion of Portugal stole the show. Its flowing concrete canopy became an unexpected new icon for Lisbon and modern Portuguese architecture.

(Pavilion of Portugal Expo 98, Álvaro Siza Image by Ben)

Two icons bookend this period: the Centro Cultural de Belém (Lisbon) by Vittorio Gregotti, Manuel Salgado and Casa da Música in Porto by Rem Koolhaas.

(Centro Cultural de Belém, Image from Therese C – Flickr: DSCN5750)

(Casa da Música, Image by Ben)

It was a time of huge construction, with Portugal racing to catch up after decades of isolation. Architects were pushed to new technical and formal limits, while the European Union kept the support flowing.

University education expanded across the country.

Projects like the Mitra Campus in Évora, the Library of the University of Beira Interior, and the Mechanical Engineering Department at the University of Aveiro showed the energy of decentralization.

(Adalberto Dias, University of Aveiro Image by Ben)

Meanwhile, Portugal’s bid to host UEFA Euro 2004 led to a boom in sports infrastructure.

One of the highlights is the Stadium of Braga, designed by Eduardo Souto de Moura — a bold fusion of a stone quarry and a football stadium.

(Braga Stadium, Image by 準建築人手札網站 Forgemind ArchiMedia (Wikipedia))

Even the Bom Sucesso Resort, a visionary project near Óbidos with 23 Portuguese architects designing 600 houses, was born in this era of optimism.

4. TROIKA (2004–2013): Crisis and Creativity

The 2008 global financial crisis hit Portugal hard.

Under the strict supervision of the Troika (European Commission, ECB, and IMF), the country entered years of austerity.

This had a devastating effect on architecture: public investments stopped, many firms closed, and big projects disappeared.

But hard times also brought new creativity.

Architects focused on small-scale, sustainable, and adaptive reuse projects — often smarter, more sensitive, and community-focused.

Sadly, even big developments like Bom Sucesso Resort faced bankruptcy.

Still, there were bright moments: in 2011, Eduardo Souto de Moura received the Pritzker Prize, following in the footsteps of his mentor Siza Vieira — once again bringing international recognition to Portuguese architecture.

5. WI-FI (2014–2023): Digitalization and Sustainability

Today, Portuguese architecture is fully plugged into global trends: smart technologies, environmental responsibility, and cultural sensitivity are front and center.

After the crisis, European funding helped Portugal recover, leading to new infrastructure projects and cultural initiatives all over the country.

Architects embraced sustainability, regional development, and innovation — while also facing growing challenges like housing shortages and tourism pressure.

Some of the boldest recent works include the Arquipélago Contemporary Arts Centre in the Azores, the restored Bolhão Market in Porto, and the Campanhã Intermodal Terminal.

In the wine and olive oil sectors, new spaces like Adega Azores Wine Company and Adega 23 have blended architecture, sustainability, and tourism.

A new generation of architects is pushing the boundaries too, with smaller but powerful projects like Six Houses and a Garden by fala atelier and House Over the Hills by Diogo Aguiar Studio.

Final Thoughts

Looking at the past 50+1 years, it’s clear that architecture in Portugal has never just been about buildings.

It’s about democracy, community, creativity, and resilience — from the dreams of 1974 to today’s smart and sustainable designs.

If you ever have the chance to visit Casa da Arquitectura in Matosinhos, I highly recommend it. This exhibition goes till September 2025

It’s a journey through history, but also a window into the future.

I hope you enjoyed the time travel,

Ben